Fire and cooking technology … and the dawn of humanity!

Fire and cooking technology … and the dawn of humanity! What on earth could these things have to do with one another?

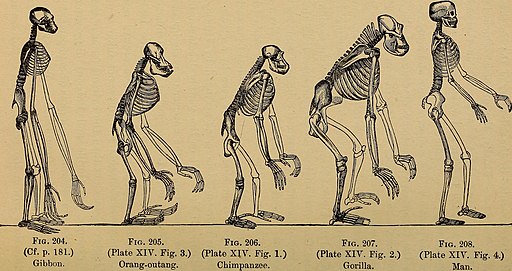

Well, when it comes to thinking about our evolutionary origins, there’s an intriguing theory developed by the primatologist Richard Wrangham. And this theory centers around an innovation we may take for granted nowadays: fire and cooking technology. In short, Wrangham theorizes that the ability to cook played a key role in the evolution of certain Homo species (such as Homo erectus), from which Homo sapiens, or humans, descended. Here’s how …

From meat eating to cooking

Many scientists theorize that meat eating played a role in the evolution of what Wrangham refers to as Habiline (a.k.a. Homo habilis, an ancestor of Homo erectus). However, Wrangham doesn’t think meat eating entirely explains the later emergence of Homo erectus (and eventually of Homo sapiens). Cooking, however, may explain that later transition.

The innovation of fire and cooking technology

By using tools to cook vegetables and meats over fire, our ancestors got (as businesspeople might put it) more bang for their buck. That is, they got more nutrients and calories for less chewing and digestive effort. Perhaps the benefits of properly cooking meat are obvious enough (we’re less likely to get food poisoning from bacteria). But cooking plants also yields nutritional and health benefits.

Indeed, this fact surprised me when I first learned it: cooking vegetables increases the amount of nutrients your body absorbs from them. For instance, by cooking tubers (thick, round stems of plants such as potatoes), our ancestors were able to increase the amount of energy obtained from eating those foods. In sum, they absorbed more energy (thanks to easier digestion) for less effort (thanks to reduced chewing or mastication).

With the discovery of cooking, human ancestors could absorb food without their guts and jaws needing to work so darn hard. By easing up that burden, more energy was freed up for other areas of the body, including (you guessed it) the brain! And that freed-up energy was significant, because the human brain uses up lots of energy—more than any other organ in the body.

The result was that our cooking ancestors evolved smaller teeth, jaws, and guts, and they grew larger brains. Consequently, they developed enhanced strength and smarts to survive longer, reproduce more, and conquer a wider range of environments.

Externalizing digestion with fire and cooking technology

In our time of manifold diet trends, Wrangham’s theory may sound counterintuitive. However, it meshes well with nutritional science. For instance, cooking can preserve antioxidants, soften fiber, and transform difficult-to-digest carbohydrates into absorbable calories (contrary to what raw-food fads claim).

In conclusion, cooked meals can give our bodies more nutrients than raw diets. The reason: fire and cooking technologies help us properly prepare foods that our digestive systems aren’t perfectly equipped to handle on their own. Wrangham’s “cooking ape” theory, which he argues at length in his book Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, essentially comes down to the idea that our ancestors discovered cooking as

a technological way of externalizing part of the digestive process (Wrangham, 2009, p 56).

As a result, their digestive processes could work less, as more energy became available for their brains. So perhaps fire and cooking technology played a significant role in the evolution of human beings. Author Michael Pollan, who popularized Wrangham’s theory in the book Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation, certainly thinks so:

At bottom cooking is not a single process but, rather, comprises a small set of technologies, some of the most important humans have yet devised. They changed us first as a species, and then at the level of the group, the family, and the individual. These technologies range from the controlled use of fire to the manipulation of specific microorganisms to transform grain into bread or alcohol all the way to the microwave oven—the last major innovation (Pollan, 2013, p 16).

It’s an intriguing idea. And if it happens to pique your interest, feel free to look up the references below, as well as check out Recommended Reading on other technology-related topics.

References

Pollan, Michael. (2013). Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation. New York: Penguin Press.

Wrangham, Richard et al. (December 1999). The Raw and the Stolen: Cooking and the Ecology of Human Origins. Current Anthropology, 40(5) , 567-594.

Wrangham, Richard. (2009). Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. New York: Basic Books.